Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in dogs and cats

What is dilated cardiomyopathy?

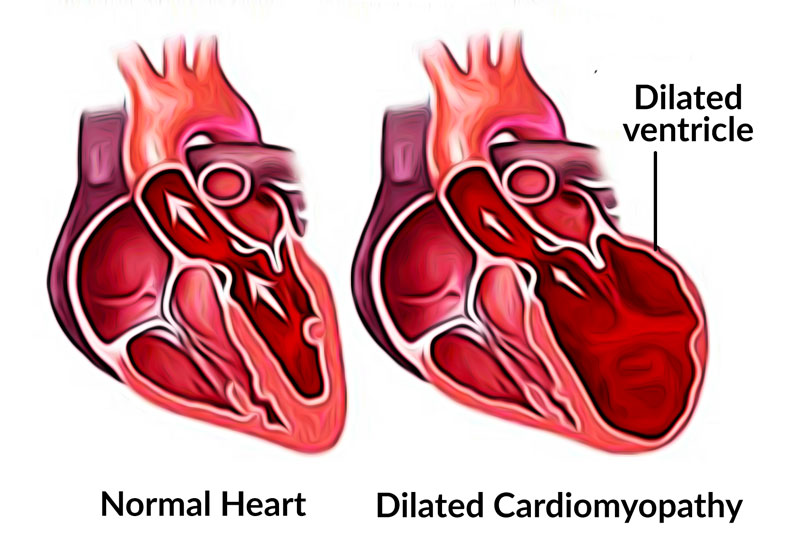

Cardiomyopathy is a disease condition of the heart muscle that inhibits its ability to function properly. In the case of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), the heart muscle is stretched and the muscle is thin and flabby, affecting its pumping ability. Dilated cardiomyopathy can affect both pets and people.

Cardiomyopathy is a disease condition of the heart muscle that inhibits its ability to function properly. In the case of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), the heart muscle is stretched and the muscle is thin and flabby, affecting its pumping ability. Dilated cardiomyopathy can affect both pets and people.

The heart is designed as a pump where each contraction pushes blood from the lungs to the rest of the body and back again. This allows the oxygen we breathe in to be absorbed in the blood and distributed to where it is needed. When the pump itself is affected, the distribution and flow of blood is compromised. In DCM, the bottom chambers of the heart, which are the power house for the pumping action, are dilated and thin, and unable to properly expel the blood presented to them from the lungs and body. This leads to a backup behind the heart. Depending on which side of the heart is more severely affected, this usually ends up with fluid and blood buildup in the lungs. In DCM, it is usually all four chambers of the heart that are stretched and affected, not just one side. This stretching of the muscle also affects the electrical conduction of the heart and its ability to pump at a normal rhythm.

How does dilated cardiomyopathy occur?

DCM is an acquired disease, meaning that an animal or person is not born with the condition, but it develops over time. DCM can be classified as:

- primary, where the cause is genetic or unknown, or

- secondary, where damage to the heart occurs as the result of toxins or infections.

Primary DCM is the most common and is seen more often in certain breeds of dogs, namely large and giant breeds such as the Doberman pinscher, Newfoundland, Great Dane and Irish wolfhound, as well as boxers and cocker spaniels.

Secondary DCM can be caused by viral infections to the heart muscle (myocarditis) or due to deficiencies in certain amino acids such as taurine (cocker spaniels) and carnitine (boxers). These causes of DCM are, however, rare in modern day due to the development of protective vaccination and well-researched and high quality pet diets.

Is there any truth to the connection between grain-free diets and heart disease in pets?

Yes, according to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) there does seem to be a correlation between the use of grain-free pet diets and the development of heart disease, specifically DCM in both dogs and cats. In 2017 veterinary cardiologists noticed a rapid increase in the number of DCM cases they were seeing. These cases were occurring in dog breeds that were not known to be genetically predisposed to DCM, such as mixed breeds, beagles, golden retrievers and even small breed dogs.

In July 2018 the FDA in conjunction with nutritionists and veterinary cardiologists began to investigate the relationship between the cases of DCM and grain-free pet diets. A strong correlation between the two were found, however the exact cause is still not known. The diets most commonly implicated were those using sweet potato or potato and legumes such as lentils and/or peas instead of grains. The protein sources varied in these diets from conventional chicken and beef to exotic sources such as bison, kangaroo or lamb. Due to the change in ingredients, it may be that an amino acid deficiency plays a role as it did in the past, or possibly that these ingredients affect the absorption or metabolism of these amino acids. The investigation is still ongoing.

How will I know if my pet has DCM?

In early cases of DCM the heart may still be able to cope and thus show very few signs of disease. It is when the heart becomes less able to cope and do its job that symptoms start to arise. At first it may be mild changes such as poor tolerance for exercise. These pets tire quickly when playing or exercising, which is sometimes accompanied by a soft cough, which almost sounds like they are clearing their throat.

As the condition progresses, signs may become more pronounced, like breathing fast and with difficulty. Affected animals may have a persistent cough, made worse by activity or exercise. You may notice fainting episodes, weight loss, poor appetite and even an increase in the size of your pet’s abdomen from fluid accumulation – also called ascites. Severely affected animals are restless, unable to lie down and rest comfortably, and have very little interest in food. If the heart has reached the point of being unable to cope, leading to symptoms as mentioned above, this is called heart failure.

What should I do if I suspect my pet has DCM?

If you are concerned that your pet has heart disease, it would be best to schedule an appointment with the veterinarian. The vet will perform a thorough physical examination and listen to your pet’s heart and lungs. Some cases of DCM will present with a soft heart murmur, and if there is congestion in the lungs this can sometimes be heard too.

My dog is one of the predisposed breeds and has a family history of heart disease. What should I do?

It would be wise to consult the vet as soon as possible to have your dog screened for DCM. This would involve a scan of the heart, known as an echocardiogram, as well as an electrocardiograph (ECG), which measures heart rate and rhythm through the heart’s electrical impulses. Some vets use a Holter ECG which is strapped to your dog for 24 hours in order to get the best possible picture of their heart’s electrical activity through the day.

These tests will indicate if your dog is at risk of developing DCM, even if they show no signs of the disease. Pets at risk of developing DCM and showing early indicators are treated with heart medication. This will not prevent the disease from developing, but will slow down the rate of degeneration through medical management. This is a lifelong treatment regimen. The earlier the vet can catch the condition, the better able we are to prolong your pet’s lifespan.

What about cats?

The main cause of DCM in cats has been found to be taurine deficiency, which was identified in the 1980s. Since this discovery cat food companies have supplemented taurine in their diets, resulting in this disease being a rare occurrence in this day and age. Dogs are able to produce their own taurine from other amino acids supplied through protein in the diet and do not suffer from this malady as often, but with a few exceptions. Cocker spaniels and golden retrievers are more sensitive to taurine deficiency and may develop taurine responsive DCM. Cats on grain-free diets have been known to develop DCM.

Cats can still develop heart disease with symptoms similar to DCM, namely hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Like in dogs, heart disease in cats can be primary (genetic in cases of ragdolls, Maine coons and some American shorthair breeds) or secondary in origin due to high blood pressure and high thyroid hormone levels.

Cats with heart disease are usually seen with breathing difficulty, poor appetite and weight loss. Treating these pets is usually focused on managing the underlying cause before focusing on the heart. Diagnosing a cat with heart disease is done in the same manner as dogs, discussed below.

What will the vet do if my pet has DCM?

Aside from the physical exam mentioned above, the vet will ask for a detailed history of your pet’s health, including diet, breathing difficulty and response to exercise. If there is any suspicion of heart disease the vet will likely recommend an x-ray and an echocardiogram. X-rays allow the vet to see the overall shape of the heart as well as see any changes to the lungs, whether it be fluid in the lungs (pulmonary oedema), fluid around the lungs (pleural effusion) as well as changes to the blood vessels in the chest. Where there is fluid buildup in the abdomen, this can also be seen on an x-ray.

An echocardiogram is an ultrasound scan of the heart. This is often performed by a diagnostic imaging specialist and the heart is visualised in motion. Each chamber as well as the valves can be seen and evaluated. The size of the heart chambers, wall thickness and the pumping effectivity of the heart are all measured with an echocardiogram. Often an ECG is also done at the same time, measuring the rate and rhythm of the heart.

Pets and people with DCM often have abnormal electrical conductivity of the heart due to the changes in structure and shape. This leads to an abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia). This asynchronous contraction of the heart makes for a very inefficient pump and may lead to fainting episodes as blood is not getting to where it needs to go, specifically to the brain. In severe cases arrhythmia can result in sudden death.

Can DCM be treated?

DCM is a devastating disease. Once a pet is symptomatic and in heart failure, the condition can only be managed, but not cured. The existing damage is irreversible; however, treatment does significantly improve their quality of life and life expectancy.

If deficiency or diet-related DCM is suspected, some pets will respond to supplementation and dietary adjustment. The mainstay of DCM treatment, however, is medical management. DCM can be managed through the use of heart medications, which assist the heart in coping in its weakened state. Other medications such as diuretics (medication that promotes the increased production of urine) are often combined with these to reduce the buildup of fluid in the lungs and abdomen. Blood pressure medications can also be useful. If arrhythmia is a problem in your pet, then medication can be provided to assist with this as well. Each patient is unique and treatment is tailored individually.

Following up with the vet is important, especially in the beginning to monitor progress and to see if treatment adjustments need to be made. The vet will likely advise follow-up echocardiograms and x-rays at regular intervals.

My pet has been diagnosed with DCM. How long do they have?

Any pet diagnosed with DCM is given a poor prognosis, which is especially true once pets are in heart failure. Most pets diagnosed with the condition succumb to it. The severity of the disease and the breed of pet determines their life expectancy. In clinically affected Doberman pinschers, for example, life expectancy is less than a year. However, cocker spaniels tend to progress a little more slowly and can live more than a year with treatment.

© 2021 Vetwebsites – The Code Company Trading (Pty) Ltd